02.01.2021

IT IS WITH SADNESS BUT THE ACCEPTANCE OF MERCY THAT I MUST REPORT THE PASSING OF MY DEAR MAM, LILLIAN MACMANUS.

t was one of my mother’s most important lessons to me that I should write down whatever was almost difficult to utter, even if concluded with a note of celebration or resolution.

Lillian was born in 1927 and grew up on Holmes Street off Smithdown Road, Liverpool 8, the eldest child of Jim and Ada Ablett. She survived her brother Arthur, seven years her junior and another brother, Gordon, who died in infancy. While her father remained in work with the Liverpool Gas Company through the Depression, his experiences as a prisoner of war between 1915 and his repatriation in 1919, seemed to have some bearing on his sometimes violent temperament. He was very demanding, sometimes quick to anger and often cruel to his wife and children.

The life of Ada Ablett, nee Mutch was made more difficult by several medical conditions that rapidly confined her to the life of an invalid. The responsibility to keep house for the family fell upon young Lillian.

During the two early periods of the Second World War, Lillian and her younger brother were evacuated to villages in Cheshire. These were contrasting experiences of thoughtful care and being exploited as unpaid labour. Local children did not necessarily welcome the “Townies” and on one occasion Lillian ran away and returned home to check on her mother, having been taunted by local kids that Liverpool had been completely destroyed in a massive air-raid.At 14, Lillian left school and got a job as a sales girl at Rushworth and Dreaper’s Music Shop, working in the record and sheet music department. Her interest in dance band music made her more valuable to senior staff whose knowledge only extended to classical music. In time, she was encouraged to serve as an unpaid usher at the Liverpool Philharmonic Hall to increase her awareness of the classical repertoire.

By the late ‘40s, Lillian’s interest in jazz meant that she moved on to a shop in which local musicians sought the new releases. It was there that she met Ross McManus, a trumpet player newly returned from his National Service with the RAF in Egypt.

If records have been important in my life it is because my parents met across the counter of the record shop; “Bennett’s”.

Over the next few years Lillian and Ross ran “Bop City” and other club nights in the back rooms of pubs and other venues on either side of the Mersey, as Ross became “Birkenhead’s First Be-Pop Trumpet Player” (it has to be said, that he was probably the only one too). Lillian would occasionally take the place of their vocalist at rehearsals, when the singer was late from her day job but Lillian could not be persuaded to actually sing on stage in front of an audience.

Lillian had customers determined to hear American records about which they had only read in magazines and which were subject to punishing import duty that her sales manager was unwilling to stock. On one occasion she gave her own money to Norman Milne, a part-time singer friend (later to know success as, “Michael Holliday”) who was working a seaman’s passage to New York. He was charged with obtaining Lenny Tristano & Lee Konitz records for one of Lillian’s obsessive customers and she effectively had them smuggled back into the country.

My folks married in London after both moving south. Lillian worked first in Bexley Heath in Kent and later in Selfridge’s record department, jobs which she apparently talked her way into with astonishing self-confidence, which stood her in good stead when she ended up in a heated argument with the visiting actor/director, Orson Welles, when she refused to sell him a one-of-a-kind demonstration model of any early portable record player.

Ross pursued his jazz career until he realized that a family would require the more steady employment of being a trumpet/vocalist with a dance band. He worked for both Bob Miller and Arthur Rowberry on the Mecca Ballroom circuit, the last being a residency in Leeds, during which Lillian’s early months of pregnancy were spent in Chapeltown.

My folks returned to London just before I was born, which at least spared me the indignity of being a Yorkshireman. I was born in Paddington and immediately taken north to Birkenhead to be christened in the presence of my paternal grandfather, Patrick, who was by then suffering from stomach cancer. I was baptized in the, now defunct, church of Holy Cross in the North End.

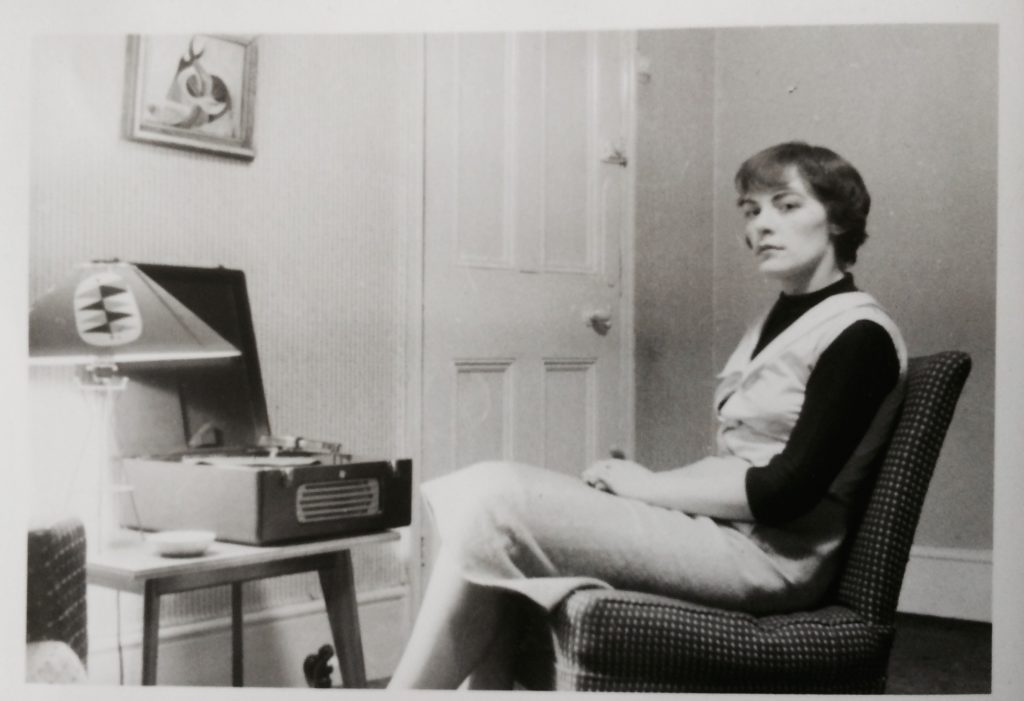

In 1955, Ross put aside the trumpet and became one of three vocalists with The Joe Loss Orchestra. My parents and their infant son lived in the basement flat of a boarding house near Olympia run by a Welsh landlady, who lived on the floor above us. It was a modest dwelling with an outside toilet and access to a shared bath but apart from joining my father at a summer engagement on the Isle Of Man, the family lived there until shortly after I entered the Sacred Heart Covent School in Hammersmith.

By this time, my Dad’s better prospects allowed us to move to a maisonette in East Twickenham, just minutes from the River Thames, which would sometimes visit the back garden in Spring.

Lillian soon returned to record retail, part-time, at Potter’s Music located at the foot of Richmond Hill, a place patronized by local resident musicians and traveling players from Pete Townshend and Mick Jagger to Peter Green.

My father was now playing nightly at the Joe Loss Orchestra’s residencies at the Hammersmith Palais, the Lyceum and The Empire, Leicester Square as well as broadcasting from the B.B.C. Playhouse Theatre, Charing Cross and occasional appearances on television for “Come Dancing”, as well as on the bill of the 1963 Royal Variety Performance alongside, The Beatles, Eric Sykes, Hattie Jacques, Buddy Greco, Flanders & Swann, the stars of “Steptoe and Son” and Marlene Dietrich and her accompanist, Burt Bacharach.

My Mam and I watched that broadcast with rather more interest in the entertainers than the Royal party, seeing my Dad dance around in an apparently scandalous, sheer off-white suit, singing, “If I Had A Hammer”, while the Queen Mother fiddled with her jewelry, even if she didn’t rattle it until John Lennon told her to do so.

Apart from these moments, Sunday lunches, while listening to “Two-Way Family Favourites”, a few early 60s holidays in Spain to which my father drove us through France and across the Pyrenees, I suppose it was only my childhood innocence that shielded me from an awareness of an estrangement between my parents.

I did sometimes overhear late night phone calls with other band wives, commiserating with each other about straying or drunken husbands and eventually my Dad was living at another address.

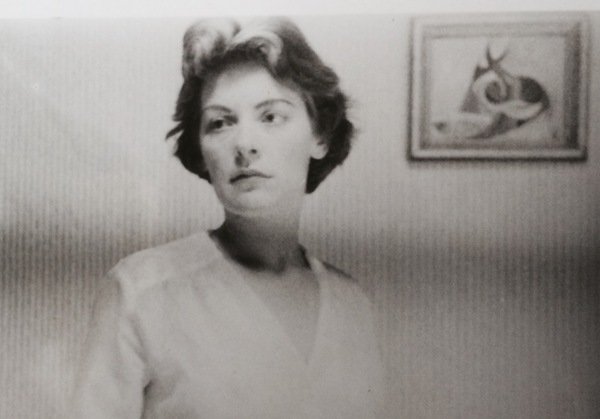

I think those mid-60s years were very hard on Lillian. There was something close to a nervous breakdown and the usual prescriptions for chemical condolences but my father continued to visit regularly and the appearance of family life could sometimes be maintained.

In 1970, my mother and I moved to West Derby in Liverpool and having worked as a computer data input clerk for the first part of my teenage years, she transferred to a new job as a personnel officer at the time when it was a job description taking in marriage counsellor, addiction therapist and a store detective.

Our means required Lillian to also work part-time in a late-night chemist in central Liverpool, a job that had its own risks, as belligerent addicts tried to negotiate excess purchases of medicines that might augment other illicit substances.

I had begun playing folks clubs and pubs around Merseyside and Lillian was a great cheerleader for my partnership with Allan Mayes in the two-man band Rusty, even helping me get to a couple of gigs in the cramped quarters of her Fiat 500.

In 1973, I left Liverpool again to pursue a rather aimless idea of a musical career and Lillian travelled in her work throughout Northern England and Scotland, after relocating to other parts of Liverpool and briefly back to the South of England. She remained active in union representation and was a member of the Labour Party until the stain that was Tony Blair arrived on the political scene.

Her first grandson, Matthew was born in 1975 after I was married to his mother, Mary and two years later my career as a recording artist and performer gave the appearance of being that of an overnight success.

In succeeding years, it has been a great pleasure to know that my Mam would be up in a box at the Royal Court with my best pal, Alan Bleasdale to see me and the Attractions or in a good seat at the Phil to see me play with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, The Sugarcanes or Larkin Poe on the “Detour” adventure on which she made the occasional photographic guest appearance on the oversize, T.V. screen central to the set. Lillian even had the best and only seat, raised up in her wheelchair onto a flight case to see me play with Allen Toussaint at The Picket, the day after A.T. and our friend, Joshua Feigenbaum had visited Lillian for tea and biscuits in her apartment in West Kirby.

While her health permitted it, Lillian loved to travel to London to see shows at the Royal Albert Hall and it is not so many years ago that she would be happy to go on to a late set at “Ronnie Scott’s” after a dinner with Diana and I and her grandson, Matt.

Lillian and I took a holiday trip together to New York in the mid-80s, where we took in a Blue Note set by one of her favorite singers, Billy Eckstine along with a couple of Broadway shows but this was perhaps less impressive than Lillian’s solo round-the-world-trip she undertook alone to celebrate her retirement, visiting Hong Kong, Australia, a prolonged stay with a childhood friend in New Zealand, returning via a visit to another friend in Carmel in California and finally, Vancouver.

This last trip was significant to Lillian, as she and her brother, Arthur were among the names in a lottery to select evacuees to Canada on the S.S. Bernares in 1940, before my grandfather withdrew his children’s names at the last minute.

As many will know, that ship was torpedoed and many of the children in transit perished and the scheme to evacuate children to Canada by convoy soon abandoned. However, several of the older girls who made the earlier successful crossings, came of age before the end of the war and married young, becoming Canadians. I think there was something about avoiding that journey that meant that my Ma believed that someone in our family might have been destined to be Canadian.

Eventually, Lillian’s health began to limit her mobility – due to severe rheumatoid arthritis and circulation issues. She came through a series of surgeries, including two for joint replacement but became more dependent on the assistance of carers in the last twenty years.

People frequently suggested that my mother might be happier in a nursing home. “She’d enjoy the company”, they’d say cheerily, “She’d play bridge”, to which I would reply, “I don’t know why you think that, she doesn’t now”. Lillian’s view was that she didn’t want to go into anywhere filled with “elderly people”.

I had to prevail on her to accept the offer of a wheelchair at airports to save her energies and gradually accept greater and safer levels of domestic care, promising that if I could afford to do so, she would never enter a nursing home unless it became completely impossible for her to dwell in her own home.

Two summers ago, Lillian suffered a severe stroke from which she was not expected to recover but she confounded this prognosis, losing the last of her limited mobility but regaining coherent, if impaired, speech and reclaiming what had seemed to have been a failing memory.

As recently as February 2020, having lost the use of her right hand due to the stroke, Lillian demanded a pencil in order to write her own name with her left hand for the first time in more than 85 years, as it had been the hand beaten in school to suppress her “sinister tendency”. As her older grandson, Matt said admiringly, “She outlived the bastards who did that”.

I have joked that this stubbornness of will might have something to do with being born on the 12th of July in the highly sectarian Liverpool of the late ’20s and having a Protestant (although not of the Orange Order) father who named her “Lillian”, something that might have been “A Boy Named Sue” proposition in some streets and perhaps explaining why my mother would never answer to “Lilly” and only her brother, Arthur, was permitted to address her as “Lil”.

A few years ago, I wrote a book that ran to 620 or more pages. A lot of it constructed a slightly romantic myth around the relationship and experiences of three generations of MacManus men, my Papa, my father and myself. I did not write in the same detail about the care with which my mother brought me up, for the most part alone.

It was Congregationalist Lillian who saw that I attended Catholic Church every Sunday until I was old enough to decide otherwise for myself. It was my mother who picked me up from the riverside after my first teenage drunken episode, it was Lillian who made sure I continued school until I sensed no further purpose to it. I came to believe life was brief and music urgent and my mother accepted that I would follow my father’s vocation and, it must be said, some of his bad example as a husband, even as she took great pride in my career and was delighted that eventually found happiness again with her daughter-in-law, Diana, bringing a greater peace and the love that I might not have always deserved.

Lillian was proud of her son and had great love for her eldest grandson, Matt. It has been a joy to know that her long life allowed her to witness the arrival of two younger grandsons, Dexter and Frank. Their Nana has been part of their lives as they entered their teenage years.

Today, our house here in Vancouver is quiet and more thoughtful, after Lillian simply went to sleep yesterday morning, without any apparent distress. Until then shown her usual will to fight but the effort finally proved too much for her energies.

As difficult as it was to say goodbye over all these many miles apart, our family has immense gratitude to Claire, Julie, Helen, Tracie, Gaynor, Tammy, Stacy, Wendy and Gaynor (II) who worked in a 24-hour care rota to make sure I was able to keep my promise that Lillian would spend her last days at home and several of whom were with Lillian when she passed. I should also like to acknowledge the NHS doctors, nurses and care assistants at Arrowe Park Hospital who cared for my mother in 2018 and the role of my colleagues, Gill Taylor and Steve and Sarah Maidment and Trudie Frith have had in coordinating help for Lillian when I was away on the road or living overseas.

Three years ago, on a warm July evening, Lillian’s three grandsons, Matt, Dexter and Frank, Diana and myself, along with our friends Toast, Rob Hill and Ian Prowse and her carers, Claire and Julie accompanied my Mam to Prenton Park to see her beloved Liverpool F.C. in a pre-season friendly that happened to fall on her 90th birthday.

Tranmere Rovers were very welcoming to us. We had supper in a guest lounge before the game. When it came time to cut the birthday cake, the club M.C. brought the entire room to attention to join us in a rousing chorus of “Happy Birthday”, which went splendidly until he got the wrong cue and led us into a final refrain of “Happy Birthday, Dear Stella”.

I said “There you are, Mam, we got you a new name for your birthday”.

In March 2020, Lillian had insisted that she was going out once more to attend the opening night of The Imposters tour that was only curtailed by the onset of the pandemic.

We all discussed the wisdom of a 93-year old attending a crowded largely standing venue on a cold, late winter night. Lillian was adamant and with the care of her team, my crew and the staff of the Olympia, she not only enjoyed the entire show from her wheelchair on a raised vantage point and after the crowds had departed insisted on being maneuvered onto the floor where she had danced in the late ‘40s when the venue had been known as the Locarno Ballroom,

From this position, Lillian was able to meet again with my bandmates, Pete Thomas and Steve Nieve, who she had known since they were 22 and 19, our tour manager Robbie McLeod, who had known her only a little less time, likewise my representative in the U.K., Gill Taylor. My agent of 40+ years, Marsha Vlasic was there, having not seen Lillian since her trip to New York more than 30 years before and then there was, Tony Tremarco, a school friend that she had not seen for nearly 50 years. It was an elating evening and one which I will forever cherish for being the last we shared at a hometown venue.

I have known several people who never knew the love of their mother or endured a painful or even violent relationship with a parent. I have so much for which I have to thank my mother.

There is not enough to show my gratitude for all she gave to me, teaching me or handing on to me so many things, from an appreciation of Frank Sinatra, before I could properly construct sentences to a relentless Protestant work ethic that has driven my otherwise incense-infused Catholic irrationality.

The passing of an older person should be more the occasion for celebrating their long life, good fortune and strong spirit but when it’s your Mam, it is impossible to keep the tears at bay forever.

So, I’ll just say as she always did to me as a child, “Nos Da, Lillian. Sleep tight. Your Loving Son. Declan”.