09.19.2023

So there was this professor in Verona who answered letters addressed to Juliet.

Well, if that sounds like the start of a tall story I suppose it is.

There was a tiny newspaper item about a Veronese academic who had taken

on the task of replying to letters addressed to “Juliet Capulet.” This

apparently continued for a number of years, until some gentlemen of the

press exposed this secret correspondence. Quite how he came by these

letters in the first place remains unclear. We can only make a guess as

to their content. After all, these people were writing to an imaginary

woman, and a dead imaginary woman at that. Perhaps they were simply

scholarly enquiries, or letters of sympathy from others disappointed in

love, or even a plea from somebody forced into an unhappy arranged

marriage. Whatever was contained in these letters and their replies, the

idea of this correspondence provided our initial inspiration.

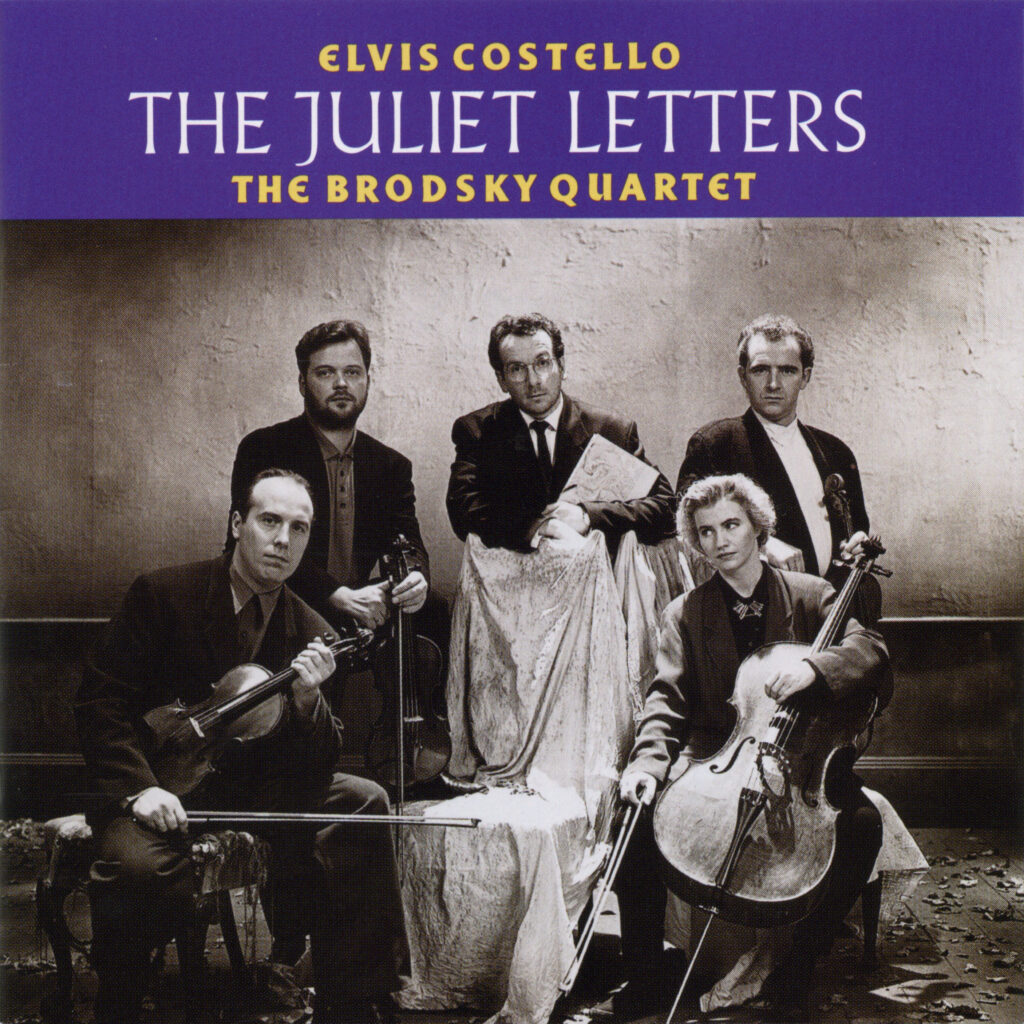

I first saw the Brodsky Quartet play at the Queen Elizabeth Hall,

London, in 1989. They were giving a series of concerts in which they

were to perform all of the string quartets composed by Dimitri

Shostakovich. Having arrived in town in time to attend the concert in

which they played Quartets Nos. 7, 8, and 9, we returned on two

subsequent evenings to hear them complete the cycle. I recall running

out of a B.B.C. television studio where I had anxiously completed a

programme presenting the album Spike in order to get to the last concert

on time. Such was the impact of these performances. Not only did I come

away with a clearer impression of the music, but also a strong sense of

the love and dedication with which the Quartet played it. Over the next

two years we went to see the Brodskys play some wonderful music: Haydn,

Schubert, Beethoven, and Bartok. Little did I suspect, but members of

the Quartet had been to my London concerts during the same period.

Somehow the connection was made, we exchanged letters and recordings,

and finally arranged to meet after their next London appearance. It was

after that lunchtime concert in November 1991 that we began our

collaboration.

At first we just talked and talked and … talked. This led to several

informal musical sessions. We looked at the characteristics of the music

that we loved and admired. The Quartet played pieces, I played songs,

sometimes we listened to records. Naturally, some of the music

introduced was unfamiliar, but this only added to the number of

possibilities. Soon our own ideas began to emerge.

We wanted to explore the under-used combination of voice and string

quartet, but were anxious to avoid that junkyard named “Cross-Over.”

This is no more my stab at “classical music” than it is the Brodsky

Quartet’s first rock and roll album. It does, however, employ the music

which we believe touches whatever part of the being that you care to

mention. It also conforms to, and occasionally upsets, the structures

found in our respective disciplines and indiscipline!

With The Juliet Letters as our title, we thought of the many types of

character that the letter form would allow us. Somewhere there is a list

of the letters which we considered. Love letter, begging letter, chain

letter, suicide note, etc. In order to make the work more personal we

decided that each of us would contribute to the text, not forgetting the

words written by Michael Thomas’s wife, Marina. As the lyricist in the

house, I could also act as a kind of editor. From these early drafts

came a curious advantage. Of course, each of us had different approaches

to the common subject, and through some unconscious poetry, and in the

absence of much of the crafty language of the songwriter, we were able

to assemble strong and varied texts. It seems that only poets and

politicians write letters with a view to them being printed in collected

form. In my experience the language of most letters swings wildly from

the lyrical to the banal and from the courteous to the confessional,

sometimes inside the same paragraph. I hope we’ve caught something of

this in the words of The Juliet Letters.

The process of composition and arrangement was varied and is mysterious

to contemplate. Some pieces arrived with both words and music complete.

Bridges were then built between smaller related items, while at least

one song and a crucial passage of the music was effectively composed

“spontaneously.” While the job of compiling and creating the “draft

arrangements” was shared among the members of the quartet, the process

of arranging was often one of trial and error involving all five of us.

This has continued throughout the rehearsals, the first two

performances, and even during this recording. Having previously been

unable to read or write down music, my own recent studies have allowed

me to progress, since January 1992, from picking out my ideas at the

piano (using what is known in certain circles as “the crab method”),

through piano scores to full proposed four-part arrangements. I have to

give credit to the Quartet for their perseverance in deciphering some of

my early intentions from the most wayward of playing. As I have found

with other collaborations, the music that you most confidently attribute

to one party invariably turns out to be the work of the person you least

suspect.

The Juliet Letters begins with a short composition entitled “Deliver

Us.” It simply serves to open the story, for although the following

letters are not intended to create a dialogue, you may choose to draw

your own conclusions from some of the resulting juxtapositions.

One of the conventions which we have taken from classical song, or for

that matter folk-song, is the acceptance of a man singing a woman’s

story. In “For Other Eyes” a woman confesses her jealous suspicions and

fears.

The “letter” in “Swine” takes a more unusual form, being a piece of

deranged, political graffiti carved on a wooden door.

For the next song, “Expert Rites,” I have taken the liberty of imagining

a reply made by a character similar to the Veronese professor who

unwittingly provided our title. If he should ever hear this piece I hope

he will not be offended by our presumption — in this version of the

mystery the author of the letter is a compassionate and romantic soul.

“Expert Rites” leads without pause into Paul Cassidy’s “Dead Letter,”

which darkens the already melancholy mood into one of sadness and loss.

After a short introduction of my invention comes Michael Thomas’s first

song, “I Almost Had A Weakness,” to which I added the tango passages. It

is an eccentric aunt’s curt reply to a begging letter.

The text of “Why?” was derived from Ian Belton’s version of a child’s

note. I added the final repeated lines and the music.

Without dragging the listener through the mechanics of our working

method, it should be stated that in naming the “main composer” we hope

to indicate who was responsible for the initial music and defining

structure of the collaborative pieces. Even if others have amended the

melodic line or added further musical content, when such a credit is

stated it is because we still regard it as “their” song. In the case of

“Who Do You Think You Are?” this credit very much belongs to Michael

Thomas. The song begins with a young man sitting down in a seaside cafe

to write a postcard in which he details all his estranged lover’s

faults. The truth of the situation is gradually revealed.

In performance, “Taking My Life In Your Hands” concludes the first half

of the sequence. The music was developed from a piece first outlined by

Jacqueline Thomas. The letter portrays an obsessive and deluded person,

writing letters never sent, expecting impossible replies.

The second part of The Juliet Letters opens with a rather extreme form

of junk mail: “This Offer Is Unrepeatable.”

The text of “Dear Sweet Filthy World” is a suicide note that turns from

blasé and bored with life to desperate, and is finally lost in a dream.

“The Letter Home” employs contrasting musical sections, predominantly

from Ian Belton (I contributed the music for only the “Why must I

apologize” section), as the story dissolves from the formal courtesies,

through nostalgia, and into bitterness.

“Jacksons, Monk and Rowe” is the name of a firm of solicitors which

reoccurs as a motif among images of both childhood and adult

disillusionment. The authorship of the two verses is divided between

brother and sister, Michael and Jacqueline, while the music is

Michael’s.

The music of “This Sad Burlesque” is mostly the work of Paul Cassidy,

although between us Michael and I proposed the related material in the

bridge section. The events described in the letter should be familiar to

those who lived in England in the spring of 1992.

The next letter is spelt out by a moving glass. “Romeo’s Seance” tells

of a strange young man’s struggle to contact his ghostly lover. He even

claims that she composed this song. In fact, the music is by Michael

Thomas, although I think I should admit responsibility for the rather

daft tune which Jacky plays during the central “flying furniture”

section. In concert performance, Michael, Ian, and Paul all play

standing up, with Jacqueline seated on a small platform. This not only

allows us to maintain eye contact, but also to change the grouping of

the Quartet in order to heighten the focus on certain unconventional

instrument balances. Without the visual aspect we decided to minimise

these changes of configuration in the studio. However, as Michael and

Jacky create most of the rhythmic and percussive interest in “Romeo’s

Seance,” Michael took up his “concert position” between the voice and

cello. Do not, as they say, adjust your set.

In “I Thought I’d Write To Juliet” a cynical writer quotes the contents

of a letter that he has received. This “soldier’s letter” is closely

related to one sent to me during the build-up to the Gulf War tragedy. I

would not like to comment further, except to say that it is not included

as a simplistic political gesture, either “for” or “against” anything,

but rather to illustrate the predicament of the two characters in being

forced to reconsider their assumed positions. From the concluding mayhem

a single note emerges leading into Michael Thomas’ “Last Post.” Despite

its title this piece does not have any military significance. It seems

to me to have a clear sense of peace, though not without strong feeling.

It also serves as a preface to the trio of songs at the conclusion of

the sequence as it runs without a break into “The First To Leave.” In

this song, a man who believes in the afterlife leaves a letter for his

atheist lover, which, we must assume, she is reading after his demise.

“Damnation’s Cellar” gives a glimpse of a fantastic kind of immorality.

The final letter is also delivered from a place beyond death, although

the intention is not at all morbid. So it is a song of condolence and

renewal, “The Birds Will Still Be Singing,” which brings The Juliet

Letters to, what I believe is, a hopeful conclusion.

The Juliet Letters was performed for the first time in public at The

Amadeus Centre, London, on 1st, July 1992, and again at The Great Hall,

Dartington, on 13th, August 1992. This recording was made and balanced

at Church Studios, Crouch Hill, North London, between 14th, September

and 1st, October 1992. It was recorded, as we say in the popular music

parlance, “live in the studio.”

Here follows a brief technical note. Our “Tonmeister” Kevin Killen, who

engineered and balanced the disc, assures us that there was no

equalisation of the signal coming from the studio. There are no

overdubbed or additional parts. In order to preserve the clarity of the

Quartet’s tone the vocals were recorded simultaneously, but behind

isolation screens. Therefore, the only artificial reverberation that you

hear is that added to the voice in order to match the natural

reverberation of Studio B. Although this was a multi-track recording,

employing a combination of close, distant, and wide microphone

positions, the very minimum of adjustments were made to the internal

balance of the Quartet in order to preserve the integrity of the

performances. The decision to make an analog recording was an aesthetic

one, founded on my firm conviction that for everything that digital

recording gains in noise reduction and supposed clarity, there are

unacceptable losses of warmth and depth. For the same reasons, the

record was mixed to half-inch analog tape. All other applicable methods

of noise reduction were employed. We trust that the results justify

these decisions.

— Elvis Costello October 21, 1992