11.02.2015

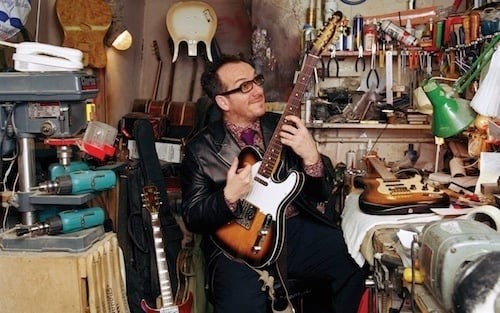

THE BUTTERFLY MIND OF ELVIS COSTELLO

Mark Ellen: 2nd November 2015

Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink is a memoir written with enough distance for Costello to reflect honestly on his extroardinary place in music.

When Elvis Costello finds himself miming “I Can’t Stand Up for Falling Down” on TV while hoisted aloft in a pantomime harness, he is filled with a sense of regret. But he was born into show business, so he knows the ropes. Hard lessons about the demands of the industry were learned first-hand as a child, standing in the wings of sticky-floored ballrooms with his lemonade and crisps, watching his father, Ross MacManus, the singer with the Joe Loss Orchestra. When Costello plays at the Hammersmith Palais in 1979, he has already had a lifetime’s experience of the tour circuit,?its familiar sour scent – as he poetically puts it, a cocktail of “spilt beer, stale tobacco, nicotine stains and, of course, the stifled tears of jilted girls”.

Fascinating connections between the fortunes of the two musicians weave their way through this beautifully written memoir. The former Declan MacManus gets an early taste of vicious press when his dad’s band becomes known as “the Dead Loss Orchestra”. He grows up with a parent who goes to work when others come home and who feels not the faintest hint of embarrassment about playing sets featuring all of the week’s hit records (from Charlie Drake’s “My Boomerang Won’t Come Back” to Pink Floyd’s “See Emily Play”). On one lively occasion in 1963, Ross returns from a Royal Command Performance mortified that the Queen Mother seemed more engaged by the rattle-your-jewellery bravado of the headliners than his toe-tapping version of “If I Had a Hammer”, but he still kindly hands all four Beatles autographs to his besotted child – the band that destroys the dance-hall orchestras inspires his son’s career.

Maybe it is observing his father, too, that makes Costello so self-aware, along with a flip comment from the blues singer Bonnie Raitt: “Girls don’t make passes at boys who wear glasses.” Even at the height of his success, a four-year tornado of world tours in support of such songs as “Oliver’s Army”, “Shipbuilding” and “Alison”, he feels that he comes across as both “smug and apologetic” but he survives through the strength and range of his magnificent catalogue.

Anyone who was electrified at the age of ten by hearing John Lennon start a song with the line “She said, ‘I know what it’s like to be dead’” is born with an extraordinary eye and ear for detail. He can conjure a whole era with a handful of words: his mid-1970s pub-rock band “had overalls and work shirts. Our conga player wore clogs.” Sometimes, he is charming and old-fashioned – “I’d arrived . . . to seek my fortune, with everything but a knotted handkerchief on a stick and a small cat under my arm” – and, at other times, he is harsh and contemporary: one record company executive had taken so many drugs that he was “trying to bite off his own ear”. Being a songwriter, he opens most chapters with an attention-grabbing explosion: “On my third day on the job, I was handed a silver whistle and told to stand outside the bank until the money was delivered”; or, “I am here to tell you that, among his many other talents, David Bowie is very good at party games.”

Anyone who has met Costello will know that he has a butterfly mind, thoughts spinning off at quick-fire, colourful tangents. The book is built in much the same way. He is born, for example, on page 81 and when he first tours the US (page 263), it sparks a lengthy diversion about his great-grandparents, who emigrated from Ireland in the 19th century (one of them is reported to have expired “of senile decay” at the age of 68). The overall effect – a pleasant one – is that the whole thing feels conversational, as if it is being related to you in a pub by the excitable author as a rambling monologue. He takes you to Wembley Stadium in 1974 to watch two of his heroes – the Band and Joni Mitchell – but this rockets him forward into memories of his appearance there at Live Aid, 11 years later, and of meeting Paul Weller backstage. This triggers recollections of a charity show they both played back in 1983, featuring U2 and the Alarm and a sketch by Harold Pinter. Moments later, we are back at Live Aid and then off to Russia, where Costello and his son Matthew gaze upon the Park of Soviet Economic Achievements from their Moscow hotel window.

His understanding of music and a musician’s place in it is never less than extraordinary. It is a fascination that rides roughshod over almost every other aspect of his life. When he is 12, he notes that Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac is “among us, not above us”; recalling his arrival at the mud-clogged Bickershaw Festival in Wigan at the age of 17, he writes: “We’d all seen Woodstock so we knew that girls ran round without their shirts on at rock festivals, a prospect nearly as exciting as seeing the Flamin’ Groovies.”

Most pop stars get to meet the people they admire but Costello ends up working with a lot of them – including Burt Bacharach and Allen Toussaint – and never loses his fan-like admiration. He duets with Paul McCartney at the White House and describes McCart¬ney’s headline slot at a show for Prince Charles (at which Costello was the support act) as being “like watching Mozart do a little gig for one of the Hapsburg emperors”. When Bob Dylan wonders if “Watching the Detectives” was about a real TV cop show, he thinks it should be the other way round: “Wasn’t I supposed to be asking . . . ‘So, Bob, where are the ‘Gates of Eden?’”

Perhaps this book’s greatest strength is that it wasn’t written too early. The 61-year-old Costello now lives in Vancouver with his third wife and twin sons, far enough from the killing floor of his early success to try to make sense of it all. To his credit, he nobly lampoons his hot-headed younger self with his “show-off rhythms and quips”, occasionally mourning “the scent of my wretched soul”. You can’t help but admire his honesty for including a mortifying moment when his first wife turns up at the Royal Albert Hall to see his “Spectacular Spinning Songbook” show, in which the set list is chosen at random when he turns a giant wheel. “Eight songs in a row were about how our lives fell apart. I betrayed her,” he admits, “and it broke both our hearts.”

He ends up aware that nearly every moment of his life was engineered by himself, and now accepts the praise or blame, though he also suspects he caused the odd train wreck deliberately just so he could write a song about it. He and his manager wonder sometimes if he should “stick or twist”. The answer, delightfully, is usually “twist”.