05.09.2017

ELVIS: HIS ‘BEDROOM’ IS MORE LIKE A MANSION

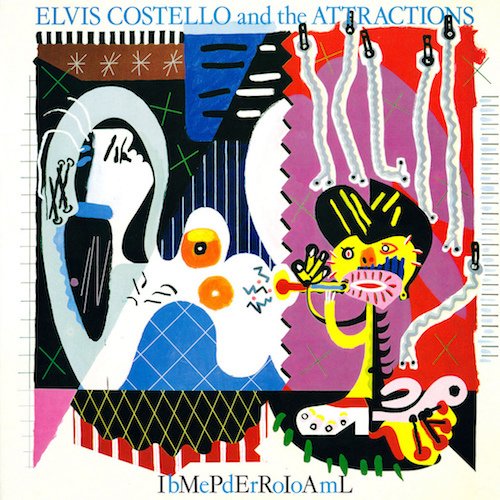

Elvis Costello and the Attractions / Imperial Bedroom

Rolling Stone: Parke Puterbaugh: August 5th 1982

After years of furious parrying with his obsessions in a long ride that’s taken him from arsenic tinged punk psychodramas to gin-mill country & western weepers, Elvis Costello has made his masterpiece. Imperial Bedroom doesn’t make its point by hurling bolt after bolt of hard-rock epiphany; rather, its intensity is cumulative, the depth of feeling evident in the hard-won wisdom of Costello’s lyrics and his extraordinary attention to musical detail.

He begins with an axiom — “History repeats the old conceits / The glib replies, the same defeats” — sung from the inside. Having cast this deterministic nod to the unchanging order of human affairs, Elvis Costello ambitiously sets out to bring new wisdom to old rituals. Casting fresh light in hidden places, he throws open the double doors to the imperial bedroom, that private arena wherein romance burns hot, and then burns out. Costello plays the canny spy in the house of love, sifting through smoldering embers for clues; twisting clichés and commonplaces, and finding truth in their ironic reconstruction; making his passion felt with the most varied and committed music he’s ever played in his life.

When Elvis Costello hit these shores in 1977 for a club tour that coincided with the stateside release of My Aim Is True, he was already more into the razor-edged material of his then-unrecorded second album, This Year’s Model. I have an indelible image of him sweating clean through a rust-colored suit by the third or fourth song; his palpable anger ignited the audience, but there was a distance there that wouldn’t allow him to connect — that is, share a conspiratorial sputter — with his zealous following. His guard was up, and his rage precluded communality. But even the bitterest alienation seeks eventual relief, and Costello, after writing countless volumes on the subject (twenty songs on a single album — twice?), gradually got happier. With Trust, the faint trace of a smile crossed his face, and on Almost Blue, he paid loving tribute to country music. With Imperial Bedroom, he’s opened the door to his heart even wider. On “Town Cryer,” this LP’s closing number, Costello sings: “Maybe you don’t believe my heart is in the right place / Why don’t you take a good look at my face.” He could well be offering a rebuttal to those who’ve consistently and wrongly judged him to be only venal, spiteful and vindictive.

While there is nothing overtly “country” in the sound of Imperial Bedroom, it evokes a pair of C&W classics — Willie Nelson’s Red Headed Stranger and George Jones’ The Battle — in its thematic concerns. Imperial Bedroom’s fifteen songs paint a sometimes droll, ofttimes grim picture of love eroded by the inevitable procession of time and temptation. Even a marriage vow isn’t sufficient glue to hold two people together. Like his C&W mentors, Costello has become an expert storyteller; he now knows that the accusing finger can often be pointed in both directions, and this has given him a newfound generosity of viewpoint. Witness “The Long Honeymoon,” in which he describes the sorrow of a woman who knows only too well what’s keeping her husband out after dark:

Little things just seem to undermine her confidence in him

He was late this time last week

Who can she turn to when the chance of coincidence is slim?

‘Cause the baby isn’t old enough to speak

The lesson of “The Long Honeymoon,” almost a throwaway line, is that “There’s no money-back guarantee on future happiness.” With the deck so hopelessly stacked, the only reasonable emotions would seem to be pessimism or rage — and, indeed, Costello has generally embraced the latter. This time, though, there are glimmers of vulnerability, unexpectedly candid admissions of yearning and need, as when the lonesome protagonist of “Human Hands” — stuck at home with only his TV set and shadows on the wall for company — blurts out, “All I ever want is just to fall into your human hands.”

Imperial Bedroom is not all doleful lamentations, however — not by a long shot. Though its narrative preoccupation with scenes of domestic blistering recalls the oeuvre of Jones and Nelson, it’s got a potent, articulate musical kick that summons the heady spirit of such seminal Sixties rock masterworks as the Who’s Tommy, the Pretty Things’ S.F. Sorrow and, yes, the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper. Like those records, Imperial Bedroom achieves depth and resonance by presenting a stylistically varied musical program rich in ingenious arrangements and strong melodies. Thus, the glib barroom singalong of “Tears before Bedtime” is juxtaposed with the sobering judgments of “Shabby Doll,” whose jazzy, staccato piano chords and wandering bass give the song a disembodied air. Four songs on side one are linked by a frantic segue — amphetamine guitar and wordless screaming from Costello that sounds like the howl of the id, the rage beyond words that lurks in the upstairs of the psyche, counterpointing the deliberate, rational voice of those numbers it interrupts. And the eight songs on side two brim with an effusive vigor that takes some of the sting out of Costello’s more rancorous lyrics.

Due credit must go to Steve Nieve, who orchestrated many of the songs and whose keyboards predominantly color in the sour d. Mention should be made also of Geoff Emerick, whose full-bodied, wide-screen production gives Costello ample room to sow his plangent visions. The paramount instrument, though, is Costello himself: he makes his voice over into a hundred voices, from reverberating chest tones to plaintive wailing at the top of his range. He cajoles, pleads, remands; turns passionate, then contrite; whispers a confidence, rails at betrayal. In one of the album’s most telling moments, he drops the mask of insolence and revenge to confide, “So what if this is a man’s world / I wanna be a kid again about it.”

Elvis Costello’s Imperial Bedroom is really a mansion, each of whose rooms is decorated with painstaking care and detail by the artist. In every aspect of this masterfully wrought, conceptually audacious project, he’s managed to bulwark his emotional directness with vision and clarity — and to make an album that lingers and haunts long after the last note has died out. Like a long, episodic novel — or a long, episodic relationship — you can look back when it’s over and measure how far you’ve traveled.