11.30.2015

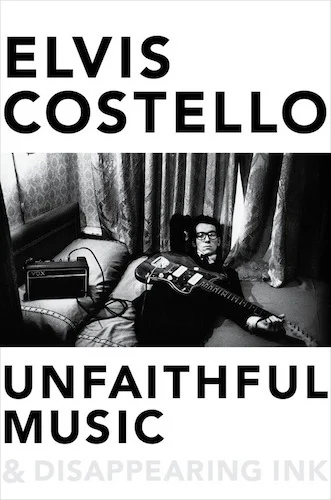

ELVIS COSTELLO UNFAITHFUL MUSIC & DISAPPEARING INK

RTE Ten: Paddy Kehoe: November 2015

“I was also deliberately using words in a manner that did not always accumulate to literal sense. I reasoned that there could be multiple realities and moral perspectives, tenses and genders all in the same verses, telling myself that if you could do this in painting, then you could do it in song.”

Whoa there, this isn’t your common or garden rock star writing his 672-page memoir, his Christmas doorstopper. We are not even talking ‘rock star,’ because Declan Patrick MacManus, aka Elvis Costello, is a kind of polymath of music who would of course curl his lip, Elvis-like, at the phrase ‘rock star.’

Noddy Holder, once the charismatic front-man with Slade, has also written work-related books. We doubt somehow that he would get into the kind of nuanced articulation quoted above, which can be found on page 69 of the very fine Unfaithful Music and Disappearing Ink.

So many celebrated musicians wander down the corridors or hover backstage in the pages of this vast dressing-room of a book, that it should come as no surprise that Slade come, however peripherally, into the story too, in the industrial town of Widnes, in Cheshire, circa 1971, when Costello was singing with a folk group called Rusty.

Costello is marvellous at evoking the period and that self-deprecatory note and sense of theatre of the absurd is firing on all cylinders. In Widnes, a few girls nursing Babycham asked – with a sneer – if his group knew any Slade songs. “None of our songs bore any resemblance to Come on Feel the Noize, so we gave up on Widnes, or maybe Widnes gave up on us,” Costello ruefully recall

Fast forward to 1974 and Elvis is going to see headliners Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young in Wembley Stadium, with The Band and Joni Mitchell also on the bill. He pays particular attention to The Band. “I was astonished to see that Robbie Robertson was playing a rock star guitar like a Stratocaster, rather than the Telecaster he’d always been shown playing in photographs, “ he notes, as, of course only the hyper- circumspect EC would.

“Seeing those shots and hearing the shrill, piercing cries that I had assumed came from that guitar was the whole reason I’d finally traded in my Les Paul copy for a brand-new Fender.” Ah yes, Declan, we feel your pain. Around this time , he was playing in what would become known as a `pub rock’ band called Flip City. They were modelling themselves on Brinsley Schwartz, and doing a set that included Hank Williams and Gram Parsons songs.

Paul McCartney, Al Green, Alain Toussaint, Chet Baker, Bob Dylan, Roy Orbison, Johnny Cash, Bruce Springsteen and many more folks you will recognise number among the glittering cast of characters, but always somehow placed in measured perspective by the memoirist. While there are some interesting sidelights into his personal life – a holiday in Russia with his son Matt, exploration of the conflicted relationship between his parents – the book mostly confines itself to the amazing musical odyssey. Costello once sneered the words ‘Stairway to Heaven’ into Robert Plant’s face, which the Led Zeppelin singer reminded him about years later. Plant had thought to punch the young upstart on their first encounter but apparently thought better of it.

The curious thing is that Costello loved lots of music in truth that really doesn’t remind us directly of the sublime, immortally impish music he cut with The Attractions, the band with which he is most associated. Clearly it all went into the mix and what came out was the glorious result of years of intense listening to pop – he loved The Beatles – jazz and blues and country.He recalls his admiration for early Elton John records, for instance, which would have been hard to credit as we listened to Get Happy. Elton would later become a great friend and Costello says he could write a book about his generosity and kindness.

He recalls his passion for Van Morrison’s Tupelo Honey and Band and Street Choir albums, he marvels at the `muffled pulse’ of Mick Fleetwood’s drum on Man of the World. He raves about Peter Green’s playing on the latter track and, years on in the middle of his own thriving career, sees the blues guitarist on a London street, looking dishevelled and forlorn, his finger-nails grown long, a genius abandoned.

Costello’s musician father, Ross McManus, looms large in the story and the portrait is brilliantly executed. The author was at his dad’s death-bed and he can break away from the surreal larks that characterise much of the first section to write prose of immense feeling when dealing with such a scene.

But thank God for Costello’s acerbic sense of humour which makes the experience of reading his memoir such scurrilous pleasure as you read first-hand of the anarchy and insouciance of being an Attraction at large in Tokyo and in the USA.