10.07.2015

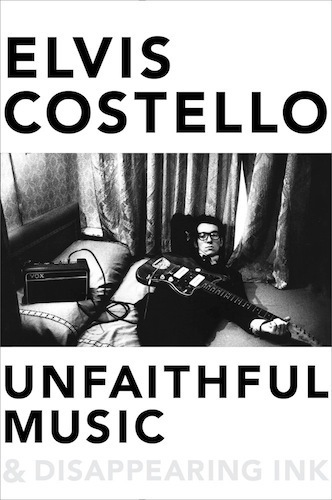

ELVIS COSTELLO HAS A NEW MEMOIR, AND IT’S EVEN BETTER THAN BOB DYLAN AND KEITH RICHARDS’S BOOKS

The Washington Post: Geoff Edgers: October 6th 2015.

It’s 1979, and Elvis Costello, not yet 25, is in on a creative roll. With his Buddy Holly glasses and punk rock sneer, he already has established himself as a masterful songwriter, whether crafting torchlight ballads (“Alison”), tortured kiss-offs (“Lipstick Vogue”) or biting protest songs (“Oliver’s Army”) as buttery as anything in ABBA’s catalogue.

Naturally, our hero is also a mess. He’s drinking too much, separated from his wife and embarking on a series of dysfunctional relationships. “I once referred to this process as ‘Messing up my life, so I could write stupid little songs about it,’ ” he says, “and I can’t improve on that description here, but then songs are never exactly taken from life.”

The paragraph, sprung midway through Costello’s sprawling memoir, gets to the heart of what makes “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink” so fascinating. We get the artist when he’s old enough to have perspective, but still young enough to remember every detail, down to the shirt his father wore (“embroidered . . . with small mirrors sewn into the fabric over a scoop-necked Mickey Mouse T-shirt”) during a meeting in London more than 40 years ago.

In a world littered with uneven (and largely ghosted) celebrity memoirs, “Disappearing Ink” is a beautifully written revelation. Dare I blaspheme by declaring I liked it even more than the excellent memoirs produced by Bob Dylan and Keith Richards? Costello embraces the basic qualities of good storytelling: the use of detail, tension and humor. At 672 pages, “Disappearing Ink” is actually a breeze.

The book is also a gold mine for Costello obsessives who have spent decades dissecting and analyzing his every lyrical zinger. But it’s not just for fans, more “Angela’s Ashes” than Motley Crue’s “The Dirt.” “Unfaithful Music” is a lyrical tale that stretches across generations, geography and a century of popular song. The book serves as both a musical and personal anthropology. Young Declan MacManus who, in 1963, squirrels away a napkin signed by the Beatles, becomes Elvis Costello, a man enlisted, a quarter-century later, to write songs with Paul McCartney.

George Jones. Solomon Burke. Nick Lowe. Van Morrison. Burt Bacharach. The Brodsky Quartet. The Specials. The Roots. Allen Toussaint. Lee Konitz. Bob Dylan. They’re all here — and not to drop names but to connect the musical dots. After reading of Costello’s more obscure influences, you also might find yourself searching out records by David Ackles, Tim Hardin and Georgie Fame.

Wisely, Costello busts the chronology. His rich family history — much of it centered on his father, Ross, a singer and trumpet player of some prominence — is presented in the context of his creative life. And for a songwriter who could fill the cargo hold of a Boeing 747 with clever puns, it won’t be surprising that Costello, the memoirist, has a gift for the punch line. He fails to score Rolling Stones tickets for a 1971 concert, declaring with teenaged snootiness, “They’re probably past it,” and decides to spend the cash he has saved on a record. “All of which would be a good story if the record I purchased had been something more inspiring and enduring than ‘Volunteers’ by Jefferson Airplane.”

He watches McCartney, during a benefit concert in 1979, curiously instruct his bloated superstar, “Rockestra,” to wear silver top hats and tails, while the well-lubricated Pete Townshend angrily signals his displeasure with a series of windmills. There’s also Costello’s wonderful description of the programmers in the computer lab in which he worked in the summer of 1976. Pynchon or Martin Amis would be comfortable turning out this graph. “Their demeanor said, We are a special breed. They wore eccentric clothes, smoked pipes, and took on airs. One liked to boast of his fine roast goose. Another had an unnatural obsession with the recorded works of Demis Roussos.”

Regrets? Costello has had a few. He’s sorry for the way he treated his first wife, Mary Burgoyne, although not so generous when referring to his second marriage, to the former Pogues bassist Cait O’Riordan, or his late-’70s fling with ex-Playboy model Bebe Buell. (Buell recently took to Facebook to post her dismay with his cold account of the relationship.)

Costello also addresses his lowest public moment. In 1979, at a Holiday Inn during a tour stop, he gets into a drunken brawl with members of the Stephen Stills band during which he refers to James Brown and Ray Charles with a racial slur. Here, Costello offers a series of potential defenses, from his poor psychological state to his obvious record of collaboration and admiration for black artists, before conceding “never mind excuses, there are no excuses.”

That humility is important. It’s hard to imagine it coming from the wiry ’70s-era Costello, with the oily mullet, skronky Jazzmaster and raised fists. This Costello is a grown up, grateful for what he has (his boys; his wife, Diana Krall) and blessed by the musical places he has been able to go. The man who sang so harshly about the industrial radio complex when there actually was a viable radio network isn’t about to wallow in nostalgia.

“The danger of regarding any point in the past as the golden age is that you forget that there were just as many crooks, crackpots, and idiots around then, and just as many terrible records,” he writes. “We only recall the ones we love.”