10.12.2016

ELVIS COSTELLO EXPLORES ALL SIDES OF HIS CATALOG AT MAJESTIC THEATRE

Star Telegram: Preston Jones: October 11th 2016: Photo By Joyce Marshall

There was a moment, near the end of Elvis Costello’s second encore Tuesday, that perfectly encapsulated his artistic dichotomy.

First, he sang Jimmie Standing in the Rain, a plaintive, sentimental tune from Costello’s 2010, T Bone Burnett-produced LP National Ransom, which was preceded by a poignant story about his grandfather, Pat MacManus, and how he owed him his love of music.

Near Rain’s conclusion, Costello stepped away from the microphone and interpolated, with no amplification, a bit of the Depression-era ditty Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?

The Majestic Theatre audience stood, offering Costello one of the many ovations he received over the course of more than two hours Tuesday, as the singer-songwriter mopped his brow, picked up an electric guitar and stepped back three decades, to 1986’s Blood & Chocolate, for the poisonous I Want You. Brooding and ugly, Costello spiked the menacing song with squalls of feedback and foreboding.

In the space of two songs, the 62-year-old British troubadour showcased the spectrum of his skills: A precise mingling of sweet and sour, an artist as capable of a fond look back as he is nursing a spiteful grudge.

Between these poles resides a charismatic storyteller, a man containing multitudes, who is equally comfortable regaling an audience with anecdotes of his formative, hungry, angry years — “I couldn’t believe hotels had electricity,” he joked, early on — speaking fondly about his children, or delivering barbed asides about presidential candidate Donald Trump (or, even better, reality TV: “You know pop music is a blood sport from watching The Voice every week,” Costello deadpanned. “Ugh, don’t get me started.”).

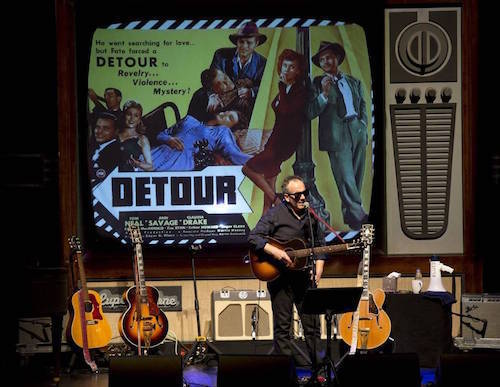

Costello’s first solo performance in North Texas in six years was part of his “Detour” jaunt around America, begun last year, on the occasion of publishing his memoir, Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink, and continued into this year.

Befitting a mostly solo showcase centered on the publication of a life’s stories, the man born Declan MacManus had no shortage of tales to tell the eager audience (albeit one that was not, oddly, at capacity; empty chairs abounded in my field of vision).

He weaved a casual narrative, more or less abandoning his story at various points, only to return to it several songs later. Rather than seeming choppy, Costello’s approach gave the night the feel of someone stretching out a visit in your living room, becoming distracted by songs but never losing track of the overall story he was telling.

The stage was busily dressed: An enormous, vintage television dwarfed the piano and multitude of guitars Costello had arrayed around him, with lighted signs on either side of the TV and several vintage microphones — including one named “Mabel,” for his late grandmother — scattered about.

He moved from acoustic guitar to piano to ukelele to electric guitar and back again, rifling through his extensive catalog and even previewing material from a forthcoming musical adaptation of A Face in the Crowd.

The familiar took on new forms — Accidents Will Happen was shorn of its pop-punk angles; the frenetic Veronica was recast as a tender acoustic ballad; Watching the Detectives was turned into a snarling, sludgy showstopper — and showcased the durability of his indelible songcraft.

The iconoclast wasn’t shy about sharing the spotlight. During his first encore, Costello was further assisted by opening act Larkin Poe (Rebecca and Megan Lovell), a pair of sisters from Atlanta, who goosed his serrated tenor with high, lovely, lilting harmonies.

As with any great story, the end arrived far faster than many in the grand old room would have liked. A raconteur of the first order, Costello could have easily kept sharing tales and tunes — revealing himself, and reflecting upon a life lived through his singular art — until some time Thursday morning.

Indeed, upon closer inspection, that supposed dichotomy — a man divided by love and loathing, torn between the dark and the light — was, in fact, masking a rich polyphony, one mood deeply informing the other, enriching both, and, in turn, all of those fortunate enough to watch Elvis Costello work.