09.15.2015

“A GREAT ARTIST SPEAKS”

American Songwriter: Jack Russell: September 14th 2015.

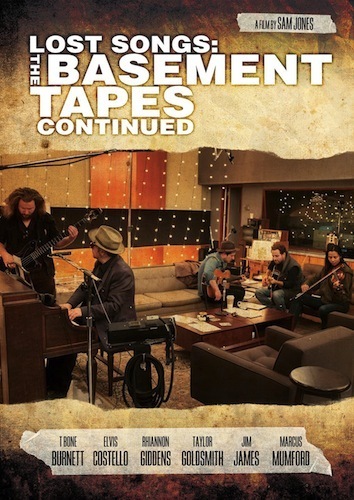

A Q&A with Sam Jones, director of Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued

In 2014, T Bone Burnett brought musicians Elvis Costello, Marcus Mumford, My Morning Jacket’s Jim James, Rhiannon Giddens and Dawes’ Taylor Goldsmith together to record a series of newly discovered Bob Dylan lyrics written just before the recording of his revered album with The Band, The Basement Tapes. These sessions were documented by acclaimed documentarian Sam Jones and turned into the Showtime documentary Lost Songs: The Basement Tapes Continued. We talked with Jones about the project’s origins, the stories he aimed to tell and what was cut during the editing process.

How did Lost Songs come about?

[Executive producer Larry Jenkins] called me and told me that they had these lyrics and they were trying to figure out what to do with them. He wanted me to collaborate on figuring out what band members should be in it, how we should do it and how we should get the people involved. It was a very exciting project for me from the beginning.

Are you a big Dylan fan?

I had a high school classmate that got me really into him when I was pretty young. And I’ve always really appreciated his songwriting. It was a perfect thing for me.

In regards to this project, it was an amazing thing that he was letting people into his dirty laundry, because there was no control. There was no, “Hey, you can’t use this, you can’t change this.” He was pretty much open to whatever, and that was pretty surprising.

Was the documentary component sort of an addition or was it a part of the project from the start?

It was there from the start. I was brought in before any musicians. I think the idea being, in this day and age, it’s sort of josh to Dylan fans. To people who love this kind of music, it obviously seems like a huge thing, but I think to the general world out there, you still need to figure out a way to be seen and be noticed and market and all that business-like stuff. I think from the start they thought, “If we’re going to get some big name people and do a high profile project, we’re going to need a film component.”

What is your general approach to filmmaking? What do you have in mind going into the process?

I think that I’m always just trying to make something that connects to people who maybe wouldn’t have been fans in the first place. The idea is, my dad, my mom or somebody that doesn’t connect to the musical genres that I find interesting could still come across a film of mine and get engaged in it and stick with it to the end. Then I’ve made a successful film. You hope that you can make a film that appeals to the die-hards and the insiders; where there’s enough stuff in there for the super die hards, but that you can also tell a story that’s universal enough for someone who’s not a fan of Dylan or a fan of any of the people in it, can still be engaged in the story.

On this particular film, I really tried to look at the relationships that artists have with each other, but also with the material and the way they struggled. And I try to put it in the context of what is universal about the creative process and that feeling of being overwhelmed by greatness and the intimidation you can feel at any level. I don’t care if you’re Elvis Costello; if you’re given these lyrics, you’re going to feel some anxiety about trying to live up to the person who wrote them. That’s something that I think anyone can relate to.

I always feel like a film at its heart is about its relatability, and can a viewer put themselves in the shoes of the characters and sort of make a comparison/contrast in real time comparing and contrasting their own life and how they would respond to those decisions and those challenges.

Were you nervous going into this project?

Not really. I think for me or probably any other filmmaker, the anxiety always comes from the delivery of something within the time that people want it delivered. Because it was a big subject, and when you start a documentary especially, but even when you start a scripted film, the material and the story and the ideas, they’re way bigger than what the final film has to be. You look at it and go, “Oh my god, this could be an eight-hour film,” so how do you chisel that down into the most lean story you can tell.

I had anxiety on how to deal with the history of the album and teaching viewers a little bit about what The Basement Tapes were originally because there’s a lot of people that just tangentially know or understand what The Basement Tapes were. So how do you tell that story and also keep people engaged in a story that’s happening in 2014. We had a pretty tight deadline, so I think the anxiety I felt was more about, I knew there was a great story there, but how do I tell it in less than two hours and do it justice?

Are there any parts of the story that you wanted to tell that didn’t quite make it into the documentary?

Absolutely, and I think that happens with every documentary and every film, really. There was a whole giant story that we spent a lot of time on about the whole bootleg industry that sprung up, because The Basement Tapes was the first bootleg. Dylan has always been this guy that has mystified his fans with all the unreleased stuff that has never seen the light of day, and this has been going on since back then, in the sense that people like Dylan and Neil Young, and [other artists] that would make whole albums but not release them.

Everyone thought Dylan had sparks coming out of his brain (and) could write 20 songs a day. This whole industry sprung up around this one record called The Great White Wonder. When you look into that story and how the music got taken out of the hands of the record labels and put in the hands of fans for the first time and that method of delivery changed, that to me was a fascinating story. We went out and interviewed all the main players in the bootleg history, and sadly in the end it was probably a two-minute, 30-second little chapter in the film.

I think also as a documentary filmmaker, you had your bets and at the beginning, you say “okay, well there’s this fascinating bootleg story,” but then you find out also that there’s this really fascinating story about this woman, Rhiannon Giddens, happening in the present. You start having to make these choices as to what you give weight to. In the end, I felt like I didn’t want this to be a historical film as much as I wanted it to be a film about the creative process. And it’s a balance thing. Our first rough cut had a lot more history and a lot more recreations and Basement Tapes stuff in it. That slowly changed over some editing.

I noticed that you gave a lot of camera time to Rhiannon, Marcus, Taylor and a lot of the people who were newer to the industry in that position where people know their names, but they’re still not Elvis Costello or T Bone Burnett. What stories were you trying to tell there?

A good story [involves] the classic elements of conflict and discovery and an arc of growth. I think that in those characters you mentioned, Marcus and Rhiannon and Taylor, they are younger and they were probably much more intimidated, honored and much more in the moment about this because it was a newer, more visceral experience for them than someone like Elvis Costello, who’s been in the studio and made 30 records. I don’t think in your 60s or your 50s that you can be changed as radically by an experiment like this as someone like Taylor Goldsmith, who still is just so excited about the songwriting process and the mystery around songwriting, or someone like Rhiannon Giddens, who really is a self-proclaimed baby songwriter. I found their stories more interesting because it was new to them.

I think for a viewer to follow a story, they would much rather have someone not teaching them and telling them how to do something, but if they can go along for the ride with somebody, that’s much more interesting. And in the case of Elvis Costello, he got the lyrics and had some time to sit with them and he created a whole bunch of demos. And Jim James works very fast, he got the lyrics and started finding old snippets of recordings he had, and he started making demos. But Marcus Mumford, I felt, was extremely brave going into this and the same with Rhiannon Giddens. Both of them were extremely brave, and they both sort of followed the spirit of the project, which they were under the impression was going to be more of a collaboration.

So they came in unprepared with the idea that they get to sit down and write a song with Elvis Costello, or they get to sit down and write a song with Jim James. Whereas some of these other people I think approached it a little bit more like an experienced songwriter would, which is “Okay, if collaboration happens, that’s great, but I’m not going to go in unprepared because we’ve got our two weeks in the studio and I’m going to do my thing and I’m not going to get out of my routine.” Once you get set working in one way, you know, Elvis Costello is not a guy that’s going to walk in and say, “Okay, what should we do today?” because he probably has more experience of how often a scenario like that is resolved in disaster and nothing coming out of it.

For Marcus to go in there and not really have anything prepared, that was true balls; and I feel the same way with Rhiannon. And she may have come in thinking, “Oh, the idea of this is we’re supposed to collaborate, and so I’m not going to prepare.” And I think that that made their connection with the material much more flexible, and it made their stories much more exciting to me.

Have you considered the possibility of a follow-up with some of the artists?

I think the film is sort of a nice little thing that’s in the present. The thing I like about this film is that there were no real exit interviews. I didn’t go back to any of them after we edited it and say, “What story are we missing?” and I like that. I like that it’s its own little encapsulated story. I haven’t really considered a follow-up.