11.07.2016

THE GREAT IMPOSTER

Lost in a Fools Paradise: Mitchell Cohen: November 7th 2016

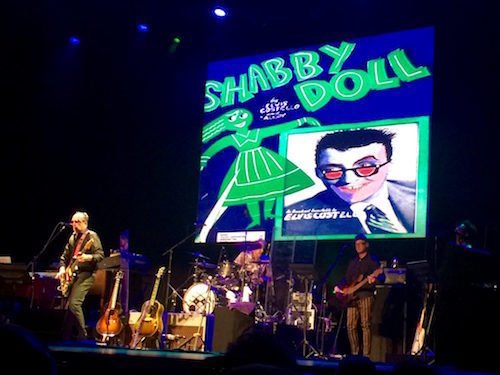

In 1977 I got my hands on an import copy of My Aim Is True and raved about it for Creem, and that began a nearly forty year off-and-on conversation with Elvis Costello, where he did most of the talking, except when I would chime in with an occasional album review. There were shows at the start (Bottom Line) and end (Ukranian Ballroom) of the first U.S. tour, and over the decades quite a number of times when I’d check on what he was up to: shows with Burt Bacharach in NYC and London, a post-Katrina benefit with Allen Toussaint, solo shows along the way, the great Spinning Wheel parties where anything was up for grabs. It’s crazy to think about how long this has been going on, because when he made himself known, there was something so urgent and immediate about it that it felt like a brushfire that might flame out before too long. It was a breathless sprint – This Year’s Model felt dashed off on a vitriolic bender – and yet not long after that (four full-tilt albums in between in three years, plus enough random songs to make up another one) came 1981’s Imperial Bedroom, and if anyone hadn’t already been convinced that Costello had long-distance potential, this was an album that you would think was undeniable: thoughtful, impassioned, maybe a little fussier than the first couple of LPs, but impressive in a different way. It was his grown-up album, written in his mid-twenties, recorded under more professional conditions with a new producer, and the collection of songs – “Man Out of Time,” “Shabby Doll,” “…And In Every Home,” a dozen more – made a decisive leap forward from his previous albums of originals, Trust (the next pre-Imperial Bedroom album, Almost Blue, was a batch of country covers, so who knew whether Costello had simply exhausted himself or not?).

Elvis brought his band the Imposters back to New York for shows at the Beacon that focused on Imperial Bedroom, but unlike the last album-centric gig I saw there, Brian Wilson doing Pet Sounds, and unlike every other recent show I’ve attended with the same basic premise (Springsteen doing The River, Stevie Wonder recreating Songs in the Key of Life), there was no attempt to treat the album in question as a text that needed to be adhered to, a sequential concert that takes away the element of surprise but lets the audience settle in on a familiar ride. With Springsteen, after a few shows, you felt as though he’d gotten himself in a trap: it was billed as a River-in-its-entirety show, and it’s a long fucking album, and once he’d done five or six songs from it, there was a mood shift in the room: Oh, this is really what we’re doing, there’s no turning back now, and the track listing lodged itself in your head. There was no reason for it. He could have announced shows that were River-intensive, and done concerts that were like the actual concerts from that 1980-1981 tour. After a while, everyone realized it was an idea that worked better in theory than in front of big, diverse crowds, so Springsteen chucked it out the car window.

That’s why the Elvis Imperial Bedroom show was such a triumph, why it should serve as a blueprint for anyone figuring out how to do the “album” show without locking in fifteen or twenty songs in an exact order (Pet Sounds is short, and flows beautifully, so it’s not as much of a commitment). Elvis stopped a few times during the set to talk about how Imperial Bedroom evolved, where the songs came from, what the recording experience was like, but he wove those songs into a broader picture, made space (the show was called Imperial Bedroom & Other Chambers) for a song from the collaboration with Bacharach, for “hits” (“Watching the Detectives,” “Every Day I Write the Book,” “Accidents Will Happen”), for Toussaint’s “On Your Way Down” and a couple of songs from This Year’s Model. You can imagine other artists doing this kind of thing, Randy Newman, Tom Waits, Neil Young, artists who aren’t so much burdened by a cluster of hit songs that they need to do (although I can’t imagine that Costello thinks he can leave a venue without singing “Alison” and “Pump It Up”), have decades of great songs, and might like the idea of the album show where the album is just a central idea, a planet around which the rest of the repertoire orbits.