10.09.2015

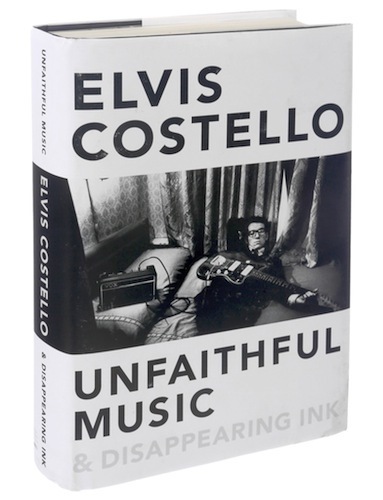

REVIEW: ELVIS COSTELLO’S ‘UNFAITHFUL MUSIC & DISAPPEARING INK,’ A MEMOIR

The New York Times: Dwight Garner: October 8th 2015

Mr. Costello’s book, “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink,” manages to be all these things, and a pint of Guinness and a bag of chips. It’s streaked with some of the best writing – funny, strange, spiteful, anguished – we’ve ever had from an important musician.

This isn’t a surprise. Mr. Costello has been cagey and word-drunk from the start. Had he not picked up a guitar, and put on the black glasses and porkpie hats, he might easily have been a poet, a Charles Simic or a Paul Muldoon.

All his promise was packed like radiation into his first hit single, “Watching the Detectives” (1977). It started, about a horrible crime, “Nice girls not one with a defect,/Cellophane shrink-wrapped, so correct.” It only got darker, and better.

Most rock autobiographies seem tossed off and phoned in: tour souvenirs. Not this one. “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink” feels as if it were written during a six-year residency at Yaddo and driven to his publisher on the back of a flatbed truck.

It is enormous. At 674 pages, it’s more than 100 pages longer than Keith Richards’s whacking “Life” (Unlike Keith, he didn’t employ an amanuensis.) It is a commitment.

This book’s nonchronological bulk, I’ll admit, sometimes seems lashed together with bungee cords. Mr. Costello foolishly tries to cram everything in, all the collaborations (with George Jones, Burt Bacharach, Questlove, Paul McCartney, the Brodsky Quartet and T Bone Burnett, just for starters), the Grammy Awards shows, the Letterman appearances.

There are pages about a TV interview show he hosted from 2008 to 2010 that few remember or care about. Mr. Costello could have used a diabolical editor, a Gordon Lish, to cut the pine from around his black opals.

But dark gems twinkle here in abundance. “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink” is highly literate yet hews to its author’s sense of what makes a vivid sound: “You really don’t need musical notation for rock and roll. I always said it was all hand signals and threats.”

Elvis Costello was born Declan Patrick MacManus in London in 1954. He was swaddled in music as much as blankets. His father sang in a popular dance band; his mother sometimes worked in music stores. His paternal grandfather had played trumpet in jazz bands on the White Star Line.

He evokes the music of his early youth with nostalgic sweetness. It’s not entirely a put-down when he says, “You could turn on the wireless in 1961 and believe that it was still 1935.”

He caught a glimpse of his own tangled future in his father who, he writes, “would always attempt to seduce the tallest girl in the room and, failing this, would pick a fight with the tallest man.”

Mr. Costello played in small, sometimes folky bands with names like Rusty and Flip City before pulling together, in the mid-1970s, the musicians who become the Attractions, his first backing band.

He was too skinny and awkward to be a glam-rock leading man. He also knew, he writes about recording his indelible ballad “Alison,” that “I’d never create a beautiful sound, as I was very obviously a mere mortal.” He went for nerve and directness and, as the title of his first record had it, his aim was true.

He became known as a prototypical angry young man. About seeing a ferocious Neil Young performance, he writes: “This was the lesson I took away from that day: If there is an apple cart, you must do your best to upset it.”

This book makes the case, however, that its author was never quite as angry as he seemed. “It seems that the space between my two front teeth, which made Jane Birkin, Ray Davies and Jerry Lewis so appealing,” he writes, “has had the effect of making half of what I say sound like a provocation or an insult.”

Still, “I could be an arrogant bastard back then,” he writes. “Bravado and alcohol made me amplify whatever was roasting my goat.” He adds: “I was looking to get into all sorts of exciting new trouble.”

He’s perplexed that a 1977 “Saturday Night Live” performance, in which he switched songs at the last second, became infamous. He is rueful about another early incident, when he is said to have drunkenly made racist comments about Ray Charles and James Brown in a Holiday Inn bar in Columbus, Ohio:

“I’ll have to take the word of witnesses that I really used such despicable racial slurs in the same sentence as the names of two of the greatest musicians who ever lived, but whatever I did, I did it to provoke a bar fight and finally put the lights out.”

He asks, “Does anything else that I’ve done in the other 59 years and 525,550 minutes suggest that I harbor suppressed racist beliefs?”

There are many women, “reckless and sometimes damaged,” and many long, wasted evenings in “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink.” A typical anecdote: writing the song “Accidents Will Happen” after having sex with an attractive female cabdriver who was taking him to the Mexican border.

He refers to all this as, “Messing up my life, so I could write stupid little songs about it.” The author tossed that existence aside for good, he writes, when he married his third wife, the musician Diana Krall, in 2003. They have twin sons.

We read about the making of many of his records. He sums up friends and collaborators in short, sharp strokes. (Bruce Springsteen “laughed like steam escaping from a radiator.”) He’s honest about his small magpie thefts from other musicians. He speaks about so many of the little-known songs that influenced him that you will begin to make playlists.

Mr. Costello bites off more than he can entirely chew in “Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink.” But passport and lottery ticket, this is.